Martini & Myth Part 4: Russian Revolution

Editor’s Note: August is Martini Month at Alcohol Professor! Why? Well, any day is an excuse to sip a refreshing Martini, however, in the dog days of summer, there’s nothing like a Martini to quench a thirst. Enjoy this hebdomadal sipping trip through the lens of some familiar pop cultural figures. Cheers! See Part 1 – on James Bond and the Vesper cocktail here. Part 2 on the Martinez vs. the Martini here. Part 3 on the shaken vs. stirred debate here.

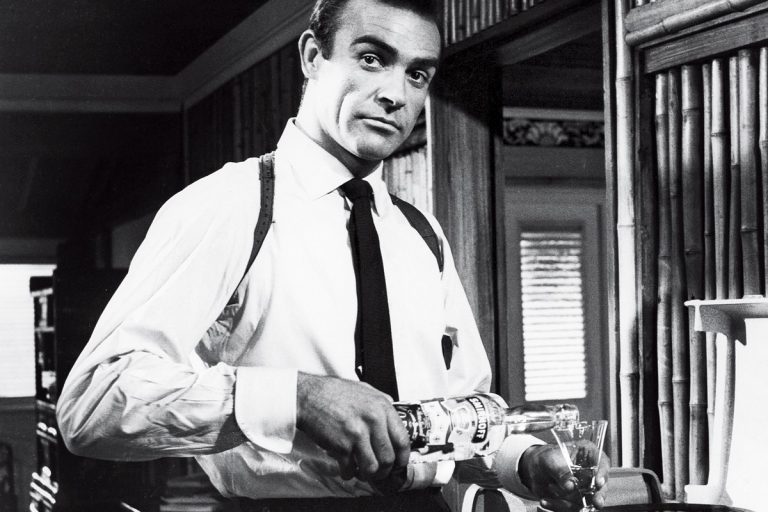

There are theories as to why the cinematic James Bond preferred vodka instead of the more traditional gin, aside from him simply being an iconoclast. Chief among them is that Smirnoff was a sponsor of the films and leaned on producers to make sure their product was featured prominently. And indeed it is pretty front and center in Dr. No. There two really famous stills from that film. The first is Ursula Andress on the beach in her white bikini. No vodka in that scene. The second is of Bond pouring himself a drink from what the camera makes sure you know is a Smirnoff bottle. Smirnoff remained a high profile partner of the films until Finlandia usurped them during the Brosnan era, but the notion that the vodka Martini came to be because of some behind the scenes deal doesn’t hold water (or vodka, for that matter). For starters, the vodka Martini made appearances in the books predating the movies. People were drinking them before Sean Connery passed the time between killings by showing the camera a Smirnoff bottle. Vodka companies were already making huge advertising pushes in the United States, and selling mid-century America vodka as a cooler ingredient than gin in a Martini was part of the package. James Bond certainly helped, but Dr. No was part of an extended strategy rather than the whole game. It’s likely Bond would have ended up drinking a vodka Martini sooner or later regardless of whether or not Smirnoff slipped him an envelope full of used, non-sequential hundred dollar bills. But getting to that point took some work.

When Ian Fleming started publishing Bond novels, vodka was persona non grata in the West. The Cold War had its first flare-up in 1950 with the outbreak of the Korean War. The same year it ended, Casino Royale was published. England and the Soviet Union may have been uncomfortable allies during World War II, but the subsequent decade put a chill on the working relationship. Then came the Cuban Revolution, the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion by the United States, and the Berlin Wall. In 1962, the world sat on edge during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The first James Bond movie, Dr. No, was also released that year. Point being, things between England, the US, and the Soviet Union were not exactly cozy. It was a very odd combination to have a blockbuster movie series about a suave British secret agent who swilled endless amounts of Russian vodka while matching wits against those self-same Russians (at least in the books, where Bond spends a lot of time fighting agents from Spetsyalnye Metody Razoblacheniya Shpyonov, also known as Smert Shpionam, or simply SMERSH). Most of the Western world, like Bond’s boss M, considered vodka dreadful communist swill, certainly nowhere near as respectable and sophisticated as good ol’ Scottish whisky. English gin, or American bourbon. Or even wine, as long as it was claret. And yet, the moment that iconic shot of Sean Connery as James Bond pouring from a bottle of Smirnoff vodka hit movie screens, the once запрещенный spirit kvodka was suddenly in vogue, Cold War be damned.

Even more audacious, it quickly became an alternative to good ol’ English gin in that most iconic of cocktails, the Martini. In the Bond novels, the Martini proper makes its first appearance in the second of the books, Live and Let Die. In the opening of the book, while Bond is relaxing in his room at the St. Regis Hotel in Manhattan, he is visited by his friend Felix Leiter, who mixes up a couple regular old gin Martinis. Later, when the two agents are at the hotel’s King Cole Bar, Leiter again orders Martinis for he and Bond, and once again they are gin Martinis (House of Lords gin, to be precise, with Martini & Rossi vermouth). Unlike the Knickerbocker, the St. Regis is still in existence, on 5th Avenue at 55th Street. Designed in the beaux arts style that was prevalent at the time, and standing eighteen stories tall, The St. Regis was the tallest hotel in New York when it was completed in 1904. Its owner was a member of New York’s premiere old money family, John Jacob Astor IV, who perished aboard the Titanic in 1912.

The hotel passed to his son, Vincent, who soon sold it to a man by the name of Benjamin Duke. In 1932 Duke expanded the hotel, adding the King Cole Bar (anticipating the end of Prohibition). The bar took its name from a mural of King Cole that hung behind the counter. The mural was not a St. Regis original. It had previously hung in another bar. That bar, as fate had it, was the one at the Knickerbocker Hotel. Although the hotel, now the St. Regis-Sheraton, changed ownership multiple times and endured many renovations and restorations, the King Cole Bar is still there, waiting for savvy secret agents to slip in and have a Martini — although the King Cole is better known for the drink that was invented there: the Red Snapper.

The Red Snapper

1 oz/30 mL Belvedere vodka

2 oz/60mL Tomato juice

1 dash Lemon juice

2 dashes Salt

2 dashes Black pepper

2 dashes Cayenne pepper

3 dashes Worcestershire sauce

Shake all ingredients with ice and strain into a Collins glass. Garnish with a salt and pepper rim and half a stalk of celery. Serve with a straw.

If the Red Snapper sounds familiar, it's because it came from the same man who invented the Bloody Mary. Fernand Petiot was a Parisian bartender plying his trade at the famous Harry’s New York Bar, where he created the Bloody Mary. During the Second World War, Petiot moved to New York, where he settled into a position at the King Cole and fully expected to put his famous Bloody Mary on the menu. The hotel’s owners did not care for the name, however. Too graphic, they thought, and simply too déclassé for the King Cole’s upscale patrons. What would that have made of a Sex on the Beach? Or for that matter, what would they have made of the juvenile sexual connotations that would later become associated with the cocktail’s new name, the Red Snapper? Or the bawdy secret contained in the iconic painting of King Cole from which the bar derived its entire identity (which was praised once by none less than Salvador Dali, who thought it the finest painting in the world dedicated to someone farting)?

It is not until the end of Live and Let Die, when Bond is luxuriating with his female conquest of the novel, Solitaire, that the iconically Bondian shaken vodka Martini drink makes its first appearance. “I hope I’ve made it right,” Solitaire remarks as she hands Bond the drink. “Six to one sounds terribly strong. I’ve never had vodka Martinis before.” But Fleming presumably had. He spent a considerable amount of time in Moscow, first as a reporter for the Reuters News Agency in 1933, covering the trial of six British engineers accused of espionage. The trial was a sham using confessions from tortured prisoners (who would later recant on their confessions, then go back to sticking by them after some additional time in the hands of Soviet secret police). In the end two of the engineers received light sentences; one was acquitted entirely; and two were expelled from the Soviet Union. The leniency in punishments in what was supposed to be an open-and-shut espionage trial for the USSR was attributed by many to the coverage of Fleming, whose diligent accounts of the trial caused international uproar at the bald-faced corruption of the Soviet justice system.

Years later, Fleming found himself in Moscow again, although this time it was only his cover that had him as a reporter. This return, in 1939, was actually at the behest of Great Britain’s Foreign Office, which wanted to take advantage of Fleming’s easy social demeanor and proficiency in multiple languages. It was while serving in this capacity that he first came to the attention of Rear Admiral John Godfrey, the man who would recruit Fleming for Naval Intelligence. It’s also when Fleming had his first drink of vodka. It’s likely, given the prevalence of vodka in the Soviet Union, that Fleming had his fair share of Martinis that substituted vodka for gin. The two spirits are about as similar as they are dissimilar (both are clear and distilled, but vodka does not have any of the juniper and botanical flavor of gin), but as pre-war vodka would have been the burlier of the two spirits, it’s far better suited for being shaken in a cocktail.

Once Bond put the final seal of approval on the vodka Martini, it became the Martini. The tables turned, and where once you had to specify a vodka Martini if that was your druthers, you now had to specifically request a gin Martini if that was what you had in mind. Ironically however, as vodka’s stock continued to rise, the Martini did not come along for the ride. By the end of the 1960s, drinks like the Martini were regarded as old fashioned by the emerging youth counter-culture. And though the 1970s saw a return of cocktail culture, it was an extremely different scene than it had been before the Summer of Love. Vodka was the superstar of the next two decades, but as a largely flavorless ingredient in fruit juice cocktails like the Harvey Wallbanger. Roger Moore's James Bond expressly avoided Martinis of any type (to differentiate him from Sean Connery) and preferred Champagne. The shaken vodka Martini resurfaced during the Pierce Brosnan run. And finally, in the 2000s, the proper gin Martini – and the Martinez, as a matter of fact – enjoyed a comeback, and the gin Martini reclaimed the name "Martini." Vodka, of course, remains extremely popular, mostly in flavored form and in fruit-flavored takes on the Martini. Say what you will about both the Roger Moore and Timothy Dalton tenures as Bond during these dark decades of cloying concoctions; at least both of them had the good sense to never, ever walk up to the bartender and ask for an Appletini… shaken, not stirred.