Martini & Myth Part One

Editor's Note: August is Martini Month at Alcohol Professor! Why? Well, any day is an excuse to sip a refreshing Martini, however, in the dog days of summer, there's nothing like a Martini to quench a thirst. Enjoy this hebdomadal sipping trip through the lens of some familiar pop cultural figures. Cheers!

The Martini has been around since the mid-to-late 1800s. Its life has spanned the Industrial Revolution, two world wars, Prohibition, the Great Depression, the Summer of Love, disco, punk, and Hammer Pants. It has been in style, out of fashion, and subject to the peculiar and not always trustworthy whims of the American drinker. Its ingredients have been altered over the decades to compensate here for a shortage of one ingredient, there for an overabundance of another. Like many of the most famous cocktails, the Martini is at its foundation and most widely accepted recipe, exceptionally simple: gin and vermouth, with an olive or twist of lemon peel for garnish. Stirred. Nothing more. And yet as simple as that recipe is, few cocktails have as many variations and corruptions as the Martini. Chocotinis, Appletinis, Bacontinis...

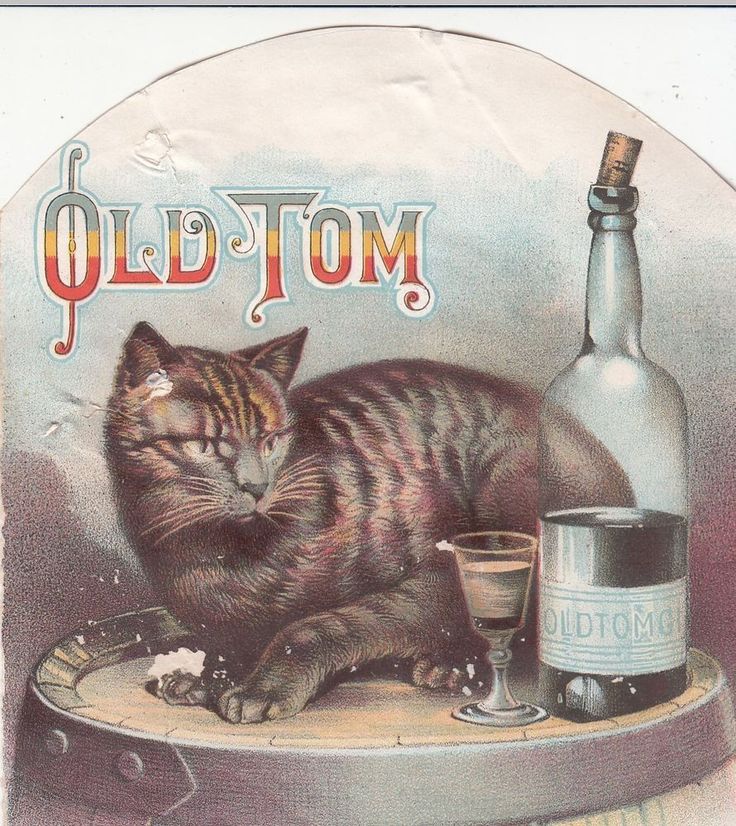

Even restricting oneself to the most basic and stringent definition of a Martini (gin and vermouth) brokers no respite from debate, as imbibers will argue about the amount of vermouth (three-quarters of an ounce? half an ounce? a wash? have the bartender inhale vermouth vapor and whisper the word “vermouth” into the glass?) and the type (dry or sweet). There isn’t even total agreement on the type of gin to use. London dry is most common — because for decades, that’s all we had in the US – but earlier recipes called for Old Tom gin. With so much time and so much alteration under its belt, the idea of pedantry in regards to the Martini seems a little misplaced, but then most pedantry does. And yet, here we are, with a cocktail that inspires sometimes comically vicious debate. At the center of the debate, often times, is James Bond’s beloved shaken vodka Martini and the Vesper – considered by more than a few to be as much a perversion of the Martini as the peanut butter Martini.

Saying Our Vespers

After its appearance in the James Bond movies, the Martini became synonymous with classic cool, a symbol of mid-century elegance. Before too long, the shape of a Martini glass (which was designed to look the way it does either because the shape helps bring out the bouquet of the gin while keeping the ingredients from separating, or because the wide opening made it easy during Prohibition to dump the drink quickly if the police came a-raiding) became the international symbol for “alcohol served here,” and neon lights shaped like the glasses became common sights outside cocktail bars.

When you tally everything up at the end of the day, there are drinks Bond consumes with greater frequency, but none of them have attained the recognizable status of the Martini. The two are intrinsically linked. Just about every novice drinker makes the social faux pas of ordering their first Martini by saying, “a vodka Martini, shaken not stirred,” while thinking they’re maybe the first (or, at worst, the third) person to order a Martini that way. More committed Bond aficionados will hit the bartender with the full set of instructions from Casino Royale, and more than a few bartenders will know what you mean when you simply ask for a Vesper.

Amazingly, until 2006, no screen Bond had ever consumed a Vesper. Other than the farcical 1967 send-up of Casino Royale, there had never been a screen Vesper Lynd to inspire its creation. At the time Fleming wrote Casino Royale, there was no big bidding war for the rights to make it into a film. The first people to give Fleming a go were American television producers, who purchased the rights to Casino Royale and filmed it in 1954 as a live television drama for the series Climax! In that early adaptation, British agent James Bond became American agent Jimmy Bond, played by Barry Nelson. But don’t worry, England. American agent Felix Leiter became British secret agent Clarence Leiter (I guess Felix wasn’t British enough), played by Michael Pate. Poor Vesper Lynd got combined with French intelligence officer Rene Mathis and became Valerie Mathis (Linda Christian). In this version, Bond orders only one drink: a Scotch and water, which he never actually consumes. He and Le Chiffre (Peter Lorre) both seem far more excited by cold, straight water. “Le Chiffre…can I have some water?” Bond inquires, to which Le Chiffre responds enthusiastically, “Oh yes, with pleasure. Basil, give him all the water he wants. Get me some water, too.”

The film rights to Casino Royale were sold again in 1955 for $6,000 to an actor-director named Gregory Ratoff. However, he never got around to making the movie. After Ratoff’s death in 1960 the rights ended up with American producer Charles K. Feldman. Feldman too was slow to move on the film. By the time he was ready to go into production, the Bond books were hits and Eon Productions, a partnership between British producer Albert “Cubby” Broccoli and American producer Harry Saltzman, had sewn up the rights to all other current and future James Bond novels. Feldman tried to sell Casino Royale to Eon, but at the time they weren’t interested. Compared to novels like Dr. No and From Russia with Love, Casino Royale is slow and a bit weepy. They'd have to put way too much time into adapting it into something filmable. Feldman decided that rather than try to produce a competing James Bond film, he would simply make Casino Royale a farce. And despite the end product of that effort containing no fewer than seven James Bonds and at least one Vesper Lynd, not a single character drinks a Vesper. And so it would remain until the 21st century.

By the closing credits of Die Another Day, Bond enthusiasts and casual filmgoers alike were exhausted by the increasingly outlandish degree of bloat that had crept into the series. In 2002, the films took a little time off and re-evaluated what it was to be James Bond in a post Bourne Identity world. In that time, things changed dramatically in the drinking world. There was a resurgence in interest in cocktails from the dusty old archives of drinking history. The internet suddenly made sharing information and enthusiasm much easier. The occasional bartender here or there interested in the drinking culture of the 1950s, the 1920s, and earlier and tired of making yet another vodka and soda suddenly found him or herself able to communicate with other like-minded bartenders and historians. From colonial punches to Prohibition classics to sleek mid-century dazzlers, the craft cocktail boom was born.

Although they'd not been interested in it in the 1960s, Eon became interested during the 1990s in Casino Royale. But the current rights holder, Sony, wasn't interested in selling. In 1999, Eon’s struggle to reacquire the rights to Casino Royale was finally settled. After nearly half a century of wandering the desert, the very first James Bond novel could finally come home — as could the first Bond girl and the drink named in her honor. 007 finally got to order a Vesper onscreen. The official recipe, to quote James Bond in Fleming’s original novel (which Daniel Craig sticks to):

A dry Martini,” he said. “One. In a deep Champagne goblet.”

“Oui, monsieur.”

“Just a moment. Three measures of Gordon’s, one of vodka, half a measure of Kina Lillet. Shake it very well until it’s ice-cold, then add a large thin slice of lemon peel. Got it?”

“Certainly, monsieur.” The barman seemed pleased with the idea.

“Gosh, that’s certainly a drink,” said Leiter.

While fans of the Bond books were happy to see the Vesper, regardless of whether or not Martini purists consider it controversial, assume its rightful place in the canon of Bond films, there were still a couple problems, all of which arise from the fact that over fifty years had passed since Fleming first committed the recipe to page. In that time, the proof of Gordon’s gin had dropped. And Kina Lillet hadn’t been available for decades. Even in the time Fleming was writing Casino Royale, the company had dropped the "Kina" (which referred to quinine which was added to the spirit) and was simply known as Lillet. Although Lillet still exists, the recipe was changed in 2006, removing the quinine entirely. Which means if you order a Vesper with the exact specifications issued by Bond, you will get a different cocktail than he got. The ship can be righted somewhat by replacing Gordon’s with Gordon’s Export (higher proof) or another common London Dry gin, such as Tanqueray. As for the Lillet, you can try using modern Lillet Blanc with a dash or two of Angostura Bitters, or Cocchi Aperitivo Americano, which has some quinine in it.

However, not getting the same drink as James Bond might be a good idea. Kingsley Amis, a storied bon vivant and the man first hired to continue the James Bond book series after the death of Ian Fleming (he wrote 1968's Colonel Sun, in which much ouzo is consumed), also wrote a nonfiction literary study of Bond, 1965's The James Bond Dossier. Amis claims that Fleming simply got his Lillets confused. Kina Lillet would have been far too bitter an ingredient, and given that the Vesper is a variation of the Martini, Fleming probably meant Lillet vermouth. And while we assume the reason Bond never orders the cocktail again is because of the betrayal he suffers at Vesper's hands, perhaps the reality is more mundane; maybe he took that first sip and realized he’d made a terrible mistake. Fleming himself lends credence to the assertion that the Vesper was concocted under mistaken assumptions. In a letter to the Manchester Guardian, Fleming issued a mea culpa regarding the Vesper: “I proceeded to invent a cocktail for Bond, which I sampled several months later and found unpalatable.”