How Archeologists Are Digging into the Roots of Wine and Making Beer

The story of winemaking is as old as humanity itself. Archeologists have been uncovering wine’s relationship to the human experience for decades, and we can safely say it dates back to at least between 6000-5800 BC.

How to Find Ancient Wine

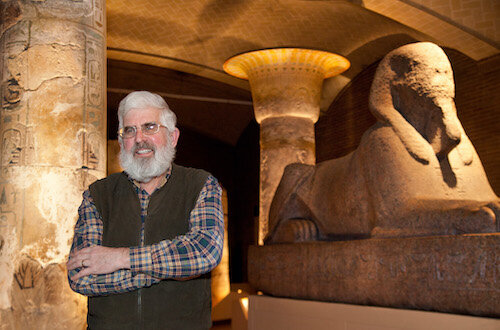

McGovern in Egypt photo AlisonDunlap 2013

Dr. Patrick McGovern, known as the “Indiana Jones of Ancient Ales, Wines, and Extreme Beverages,” has been studying biomolecular archaeological and archaeobotanical evidence for grape wine and viniculture for decades. The findings in Georgia in the South Caucasus (the earliest known wine) were a result of McGovern and fellow researchers applying archaeobotanical, climatic, and chemical testing on excavated pottery. Dr. McGovern elaborated on the process of finding evidence of ancient wine.

“You want to start with archeological sites that have very well-preserved remains. We don't want to waste time and energy on doing samples that are disturbed or contaminated in various ways.”

“We generally [examine] vessels for [evidence of] wine—generally you get the precipitation settling out materials at the bottom on the inside. Then you get a soil sample associated with it to use as a control sample. And you're interested in that base sherd from the vessel so you can look under a microscope, and see if there's any residue that's visible, but it doesn't have to be visible. It can be just absorbed into the pottery.”

“We take an organic solvent, like methanol, and we extract out compounds that are bound up in the matrix of the pottery. We usually run infrared analysis, which is passing infrared light through the sample. That'll tell us if there was any organic material. In the case of grape wine, you're looking for tartaric acid, which you can find using liquid chromatography, or mass spectrometry.”

“We look for other compounds of interest, especially herbs and tree resins with gas, chromatography, mass spectrometry. We have a sequence of analysis depending on what we find, what we observe, and what we think is possible.”

A Unique Collaboration

McGovern, the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, and adjunct Archeology Professor is a pioneer in the study of Molecular Archeology. He has traveled the globe unearthing some of the most profound evidence of ancient fermented beverages, including the reconstructing of the funerary feast at the tomb of King Midas, as well as chemically confirming the earliest fermented beverage, a mixed drink of rice, honey, and grape or hawthorn tree fruit, found in Neolithic China. In his book, Uncorking the Past, McGovern explained, “...through a number of techniques, including liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis, and infrared spectrometry, we identified the chemical fingerprints of the principal ingredients.” The presence of tartaric acid indicated ancient wine.

McGovern’s groundbreaking success in Molecular Archeology led to a unique collaboration with Dogfish Head Craft Brewery. Some of McGovern’s most important findings have translated into a line of Ancient Brews crafted alongside Sam Calagione, founder and CEO of the brewery. The Midas Touch, a brew based on the residues found in vessels in King Midas’ tomb, is the most awarded of the Ancient Ales line.

A little closer to home, Dr. Crystal Dozier, an Anthropological Archeologist at Wichita State University, is digging into possible evidence of Native American winemaking. In 2020 Dozier and colleagues published findings from the first dig in Texas. 54 pieces of pottery from six sites dating from 1300-1650 CE were examined. Absorbed residues in the pottery were put through chemical analysis using ultra-high precision chromatography. This process compares unknown molecules to known chemical signatures to narrow down possible ingredients. Their analysis showed evidence of tartaric acid and succinic acids, but results could not be replicated in multiple trials.

According to Dr. Dozier, “Caffeine and alcohol are two of the most popular substances today and are incredibly important components of religious, social, and political life in many societies. It should be no surprise that indigenous Texans also innovated, experimented with, and used these chemicals.” (Editor’s note: Anthropologists estimate that in prehistoric times indigenous peoples who are the ancestors of modern American Indians existed in Texas.).And this is just the first piece of the puzzle of Native Americans producing their own fermented beverages prior to colonization. Dr. Dozier has two other active field sites where she hopes to unearth conclusive evidence of indigenous winemaking.

Myth Busting: Native Americans and Alcohol

Dozier is on a mission to disprove the concept that Native Americans were corrupted by alcohol brought by colonizers. She wants to show they were producing, and consuming fermented beverages before settlers arrived. “The Jackson Administration perpetuated that indigenous people were naturally inclined to alcoholism. And the story [to paraphrase] was, ‘Oh, they never developed alcohol themselves. This is why it's destroying their communities. That's why we need the central government to take over and manage their lands.’ There's been a long history of this perspective of Native Americans being particularly sensitive to alcohol, which I'm not sure is actually supported by any evidence.”

With direct findings around the world of early fermented beverages, it is hard to believe Native Americans were not a part of this story. Dozier explained it may be attributed to the fact that most brewers, in all societies, were women. “Knowledge is often gendered and passed down mother to daughter. And we know the earliest European colonizers were majority men, and also particularly negative against indigenous women. So, I can understand why those pieces of knowledge have not been shared with the Western world.”

As far as the future, Dozier hopes her research challenges the stereotype of indigenous people as prone to alcoholism. “That stereotype is incredibly damaging. I hope this research helps us realize these people had similar relationships to alcohol as all people on earth, and that alcoholism is due to the repercussions of colonialism, poverty, and trauma.” Research of this kind is still in its nascent stages, and there is much to learn about the history of brewing in North America.

As Pliny the Elder said, “In Vino Veritas”—in wine there is truth. And, maybe insight into the human condition.