Reconsidering the Smashing Legacy of Carry Nation in Three Books

Carry Nation, the anti-alcohol crusader, was a nutjob who heard voices that told her to smash up saloons. She was also a towering hulk of over six feet of height, mean and ugly, and couldn’t keep a husband. Or so I’d been told, remarkably consistently, in every text and documentary I took in about the history of America leading up to the passing of Prohibition in 1920. But as I recently learned via three books, two of them just out, the truth isn’t just a nuanced variation of the first sentences in this paragraph, it’s pretty far apart from reality.

A Woman’s Place is in the Brewhouse

My first clue came from Tara Nurin’s A Woman’s Place is in the Brewhouse: A Forgotten History of Alewives, Brewsters, Witches, and CEOs

Nurin’s book is both a status check of women in the modern, mostly craft brewing business, and a historical retelling of women’s roles in brewing throughout history. The book alternates chapters between a journalistic analysis of the past few decades, with Nurin having conducted many of the interviews herself, with the chapters on ancient history beginning with the birth of beer and ending around Prohibition’s repeal.

The historical chapters cover subjects like the Egyptian goddess of beer and women’s role in brewing in ancient and closer to modern times, the now-disproven concept that alewives were the basis for the stereotypical witch with the pointy hat and broomstick, and women’s role in passing Prohibition (and Repeal) bundled with their right to vote. That is where we meet Carry Nation, “the most vilified woman of the twentieth century.” Nation is remembered for smashing up saloons with a hatchet but was, as Nurin points out, a progressive ally to people of all races and religions with a long history of charitable works both before and after the height of her fame.

Nation smashed up saloons that were operating illegally in the dry state of Kansas. She blamed the saloon owners for getting customers addicted to alcohol, and government officials and police for not upholding the laws on the books. She felt that the drinkers were victims and took the “love the sinner, hate the sin” approach to her campaigning.

Smashing the Liquor Machine

This was the first I’d heard this view of Nation, and with some Googling I stumbled upon another book, Smashing the Liquor Machine: A Global History of Prohibition by Mark Lawrence Schrad. Schrad published an excerpt from the book on Slate and in a Twitter thread. Schrad’s book covers a lot more than America’s Prohibition in its 700-plus pages, and his recent Twitter threads have covered topics like “Did prohibition doom the Russian Empire?”

Schrad reveals that Nation’s first husband died of alcoholism after only 16 months of marriage, and her second loveless marriage ended in divorce after she began her smashing campaigns. And those began only after Nation petitioned local and state authorities to uphold their legal duties. When they would not, she smashed three saloons and declared, “If I am not a lawbreaker your mayor and your councilmen are. You must arrest one of us, for if I am not a criminal, they are.” Nation was arrested 32 times in 10 years.

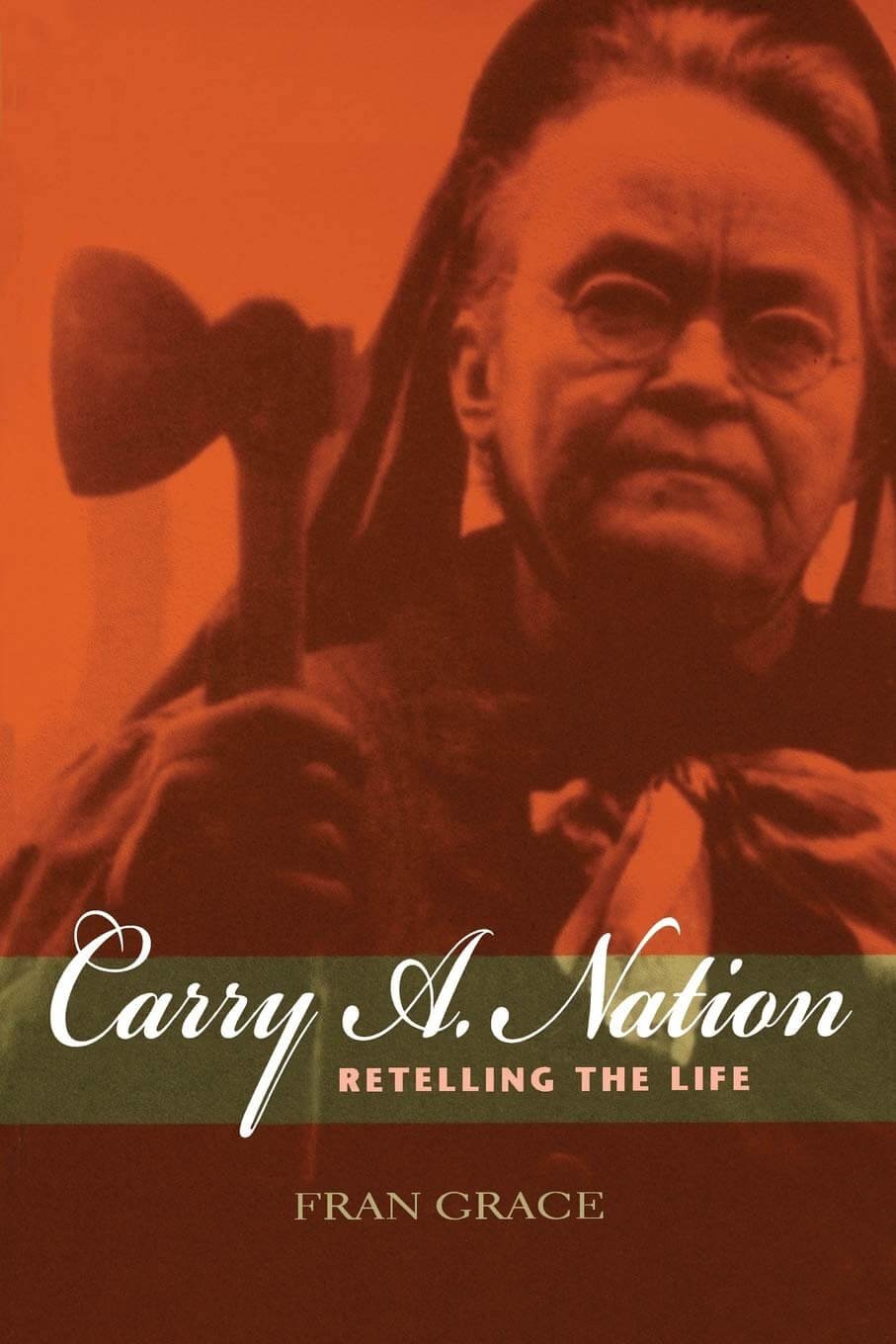

Carry A. Nation

Schrad in turn points to the first and only book about Carry Nation written by a woman, Carry A. Nation: Retelling the Life by Fran Grace, which was published in 2001. That book is a straightforward detailed biography of Nation that shows us not only her destructive phase, but also her tour on the national and international lecture circuit. We learn that Nation not only had a sense of humor about herself (her post-retirement good works center was called “Hatchet Hall” for example) but she was a master of self-promotion and sold self-published newspapers, souvenir hatchet pins, and other items to fund her works.

Yes, she claimed to have followed her god’s commands to smash up the first saloons, but so did a lot of people around 1900. Schrad points out that President William McKinley claimed that God commanded him to make war on Spain, “but we don’t teach that the Spanish-American War was due to McKinley’s supposed insanity or menopausal hot flashes.”

Via these works, it’s clear that Nation’s reputation as a masculine, sexless, insane woman was founded and promoted by the male establishment, and that most writers since her time have simply accepted that misogynistic characterization as fact. Schrad ends his excerpt, “A trailblazing social activist, she was the embodiment of the feminist empowerment mantra that ‘well-behaved women seldom make history.’ Perhaps we should start recognizing her as such.”