Boozy Book Review: Whiskey Makers In Washington, D.C.

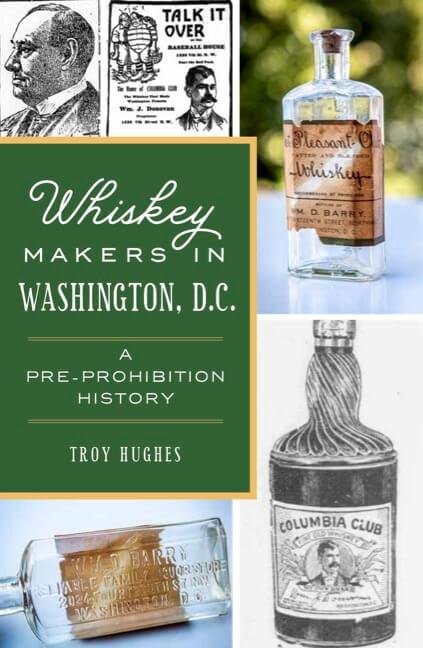

Most of the time when the subject of American whiskey history comes up it’s centered on Kentucky, sometimes Tennessee, and sometimes Pennsylvania, but almost never anywhere else. The fact is that anywhere crops have been grown is likely to have a whiskey history attached to it before Prohibition. George Washington was, at one time, the largest producer of rye whiskey in the United States at his Mount Vernon property in Virginia. Nearby in Washington, D.C., the pre-Prohibition whiskey history is less about production and more about Non-Distilling Producers, or NDPs, more commonly called Rectifiers at the time. Troy Hughes has published a book on the subject called Whiskey Makers In Washington, D.C.in which he explores the history of the Capitol’s neighborhood whiskey peddlers from pre-1917.

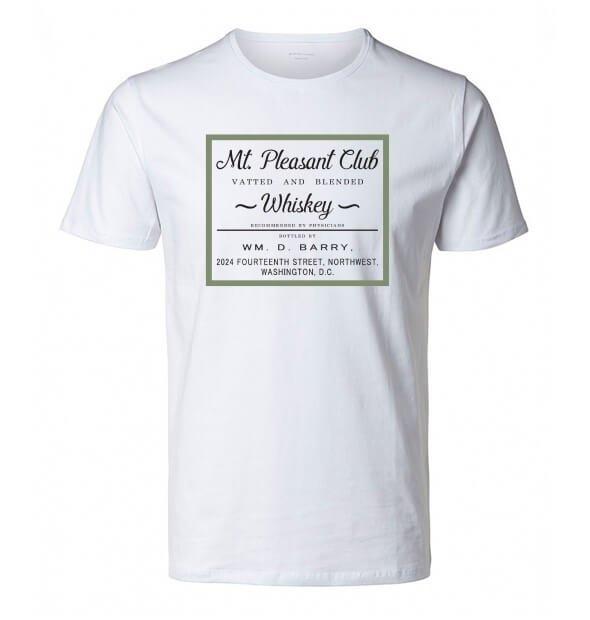

Hughes’ journey began when he moved into his current residence and the previous owner left him an empty whiskey bottle and an intriguing mystery about the neighborhood’s spirited past. He started by researching the bottle’s past and then having an artist’s rendering of the bottle put on a t-shirt to sell in his neighborhood. But his journey was just beginning.

“I honestly thought that after I made the t-shirt containing the original bottle label, that would be it,” Hughes says. “In doing some research to provide some of the historical context for the label, I stumbled upon so many interesting facts about other pre-Prohibition liquor merchants who lived in Mt. Pleasant (which at the time was a dry neighborhood). One thing led to another, and pretty soon, I had the makings of a manuscript that covered a bunch of interesting (to me at least) whiskey and DC history.”

The book opens with a quote from a straight whiskey lobbyist about the perils of rectified whiskey. “People who drink the old-time whiskey did not have stomachs disordered as they do now from drinking rectified whiskey. An old whiskey is the better and healthier. Before the introduction of whiskey made from high wines or rectified cologne spirits, with oils and flavoring extracts, a man never had the jimjams. He never drank to excess; his wife allowed him to stay at home. One drink did not create a thirst for another. The average man did not get drunk.”

Rectified whiskey

Rectified whiskey is addressed in chapter four, which controversially argues that rectifiers did not poison their whiskey, though we do know historically of some who did or at least intended to — see “going blind from moonshine,” Michael Veach’s Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: An American Heritage book which addresses “injun whiskey,” and The Manufacture of Liquors, Wines and Cordials without the Aid of Distillation by Pierre Lacour. Later in this chapter the “Poison Squad” is addressed, which adds some interesting dimension to the history of the fight between rectifiers and straight whiskey producers. At one time, it was believed by some that the fusel oils in straight whiskey were more dangerous than anything a rectifier was adding to their whiskey. This really captures the zeitgeist of the struggle between rectifiers and straight whiskey producers.

Rectified whiskey, or whiskey bottled by someone who is not a distiller, has been common since the advent of bottling and branding. There are always those who would take advantage of the opportunity to make a quick buck by whatever means necessary, and that oftentimes meant a dangerous product, but there were certainly just as many rectifiers who wanted to bottle a quality product that was safe for the consumer — a much better long-term business plan.

Troy Hughes photo courtesy of the author

“The most interesting thing I learned was that the rectifiers really got a raw deal,” says Hughes. “The straight whiskey faction, lead by Harvey Wiley, really vilified the product known as rectified whiskey, which had the lion’s share of the market prior to Prohibition. The campaign to change that fact – to include the passage of both the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 – and the subsequent battles to define “what is whiskey” as played out in the newspapers, courts, and government commissions were fascinating to me.”

Mt. Pleasant Club Whiskey

After the popularity of his neighborhood pride t-shirt, Hughes found others who had discovered similar artifacts. The curiosity would eventually inspire him to found Mt. Pleasant Club Whiskey.

“In the book, at least three of the pre-Prohibition whiskey makers (Morris, McGuire, and Drury) came to my attention via other individuals that found old bottles in their houses,” Hughes says.

Today, Hughes and his co-Founder, John Loughner, bottle whiskeys under the Mt. Pleasant Club Whiskey name with batches that are named for streets in the whiskey-producers’ neighborhoods — Brown Street after Samuel Brown, Kilbourne Place Rye Whiskey after a street in Mt. Pleasant, and more. This effectively honors the past while acknowledging the present-day whiskey distilleries in the area.

“The whiskey scene today in DC is vibrant with three active distilleries — District Made, Bo & Ivy, and Republic Restoratives — putting out a diverse array of whiskeys,” Hughes points out. “Of course, I would have to mention my company, Reboot Beverages (a non-distilling producer) as a part of this scene as well. Pre-1917, the scene went from a free for all to an atrophying market as the temperance forces, lead by the Anti-Saloon League, slowly regulated the alcohol sellers out of existence. It was so much fun to trace the whole "recommended by physicians" thread - going from producers making the claim that whiskey could be a cure for pretty much everything to being shut down entirely.”

Washington D.C. as temperance stronghold

The temperance ideology had a stronghold in Washington, D.C. according to Hughes’ book. There were many secret societies devoted to the cause, and many ominously demanded lifelong membership and fealty, or else. These societies operated in a way that was antithetical to the egalitarian ideas of the United States, pushing concepts such as “public morals” and, ironically, the Sons of Temperance donated a memorial stone to the building of the Washington Monument. But the anti-Prohibition businessfolks engaged in similarly bizarre propaganda, according to Hughes, when they cited the assassination of President Garfield by temperance supporter Charles Guiteau.

This book is about much more than just a few rectifiers in Washington, D.C. though. The chapter on Kraemer dives into the segregationist business practices of the time, including the belief that “segregation is good bsuiness.” Ultimately, homeowner’s associations and other private groups would take over the business of segregation once it was found to be illegal under the Constitution, and Kraemer’s daughter apparently bucked the system by selling her father’s DC home to a Black physician despite the neighborhood’s racial restriction covenant.

There’s also a lot about baseball that maybe borders on too much if you aren’t that into baseball.

This is a great book for anyone interested in whiskey history outside of the usual places as well as anyone interested in more general Washington D.C. history between the late 1800s and 1920. There aren’t any books on the market quite like it, though there are plenty of articles about distilling history in nearby Virginia. It covers the life and times of the people on whiskey labels, which is going to be great source material for anyone looking to do a deep-dive on any one of them.

“Mt. Pleasant Club Whiskey is today the revived brand based on the original 110+ year old bottle found in my house,” Hughes explains. “With my business partner, John Loughner, our plan is to release a whiskey for every street in the neighborhood. Thus far, we have released three batches, and have three more planned for the Fall. 2023. Working with local artists to produce labels that capture the spirit of the streets to be featured, it’s been a blast thus far putting our product out. With a bunch of future endeavors currently being planned, our hope is to slowly make Mt. Pleasant a destination for whiskey tourism.”