Irish Whiskey: The Flavors of the Republic

As we draw closer to the wearing of the green and the drinking of the brown, could there be better time to taste our way through history? We all know that green beer and shots of Irish whiskey are the staple for Saint Patrick’s Day; but why? Why is there an obligation to obliteration? This little folktale might give us a clue:

“Once upon a time a young priest walked into an inn to indulge in a pour of inebriation. The drink was Uisce Beathe (Ish-ka-ba-ha) Gaelic for 'The Water of Life.' When the priest noticed the barkeep’s meager portion he proclaimed an evil spirit had taken home in the cellars of the inn and that the only path to redemption for the barkeep was to show generosity by way of stiffer pours or the spirit would surely feast on his soul. He then left the barkeep terrified but upon the priest’s next visit he noticed a packed tavern with flagons filled to the brim. He found the barkeep and the two of them journeyed to the cellars. Here the priest announced that the spirit had been banished to the nether regions of hell and from that day forth people would drink to him on his feast day.”

Modest guy, right? I suppose being Saint Patrick could make anyone a bit cocky, but beyond shots once a year, what do most people really know about Irish whiskey? Even some serious whiskey drinkers know very little, so a few weeks ago I decided to hold a history lesson at Saloon in Somerville Massachusetts. I wanted to wander the whiskey trail via the road of the Irish. What I found was that the Pappys, the Macallans and the Johnny Walkers all owe a great debt of gratitude to the Irish, for if it had not been for this humble pour of Uisce Beathe consumed by Saint Patrick, we would not have the drams we have today.

This Usice Beathe which was later bastardized by the British to “Uski” is what we now call whiskey. But at the time of the Saint, the spirit was different from the whiskey we know today. It was known as poitin (Poo-cheen), which literally means “from the pot” referencing the type of still used.

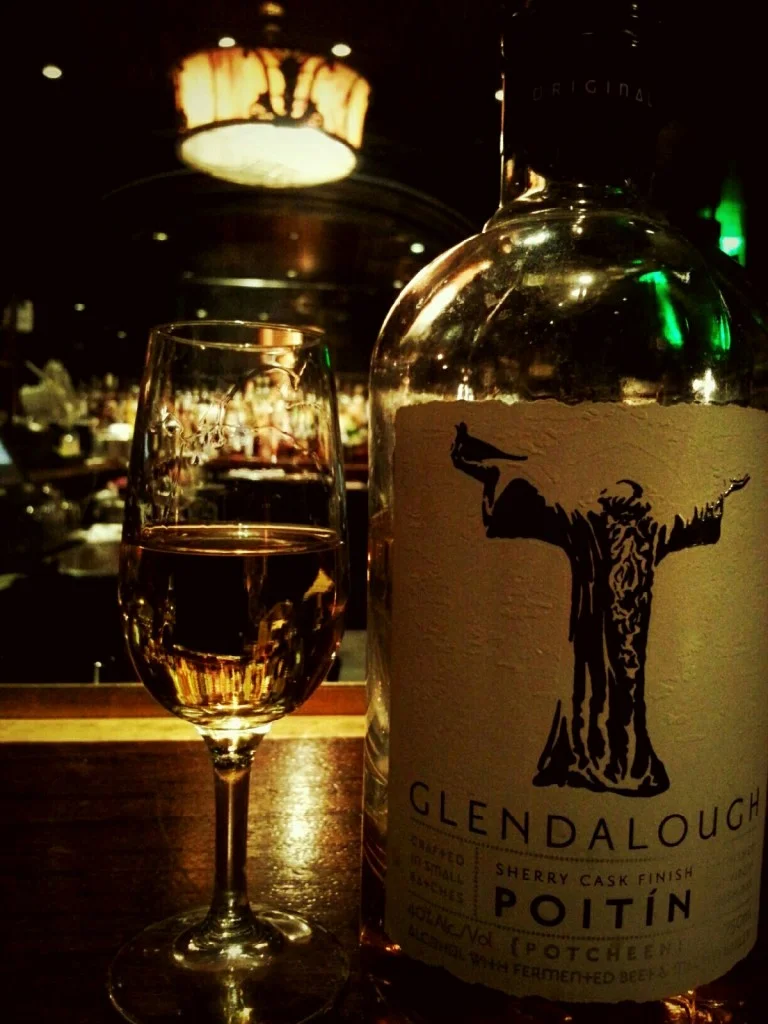

This was the dram of choice some 1500 years ago. The base of poitin, like whiskey, is malted barley, but unlike modern whiskey, it has a good portion of sugar beets as well, which can really kick start fermentation. This first evolution of whiskey was a bit rough. It wasn’t until the French taught us the technique of double distillation that a purer, cleaner spirit was made. This was the drink of the countryman, the laborer’s bread. As a result it was not taxed by the British Government and so in 1661, King Charles outlawed the drink and it was pushed into the far reaches of Irish lore, hidden in old farm houses. It became the dram of legends, a memory in a grandfather’s recollection of his grandfather. The Glendalough poitin Sherry finish has a very subtle wine note to it. You can pull off some of the oxidized sherry aromas with

delicate notes of spiced cake, honey and orange peel. When I decided to pour this, I had no idea how it would be received as one could think it an acquired taste. After we tried this, I had to remind people not to shoot it like people typically do with Irish whiskey, but at least no one flinched. In fact, they seemed to enjoy it.

Dram 2: Tyrconnell Single Malt

Once King Charles banned poitin Irish whiskey began to resemble the whiskey of today. Whiskey made of 100% malted barley was now the staple. The barely was steeped in water until a tiny sprout popped through the hearty husk. This housed all of the rich maltose sugars which gave power. A 7%ABV (alcohol by volume) beer-like brew was first distilled to a rather low level of 25% ABV in what is called the “wash still”. It was then introduced into a “spirit” still taking a humble, awkward liquor into a rich, oily, strong water known as “new make spirit” which would be roughly 65% ABV. From here it would go into barrel to be aged. Once it was determined that the spirit was ready it would be cut down to the more approachable strength to be sold off around the world. Tyrconnell Single Malt is hands down, one of my favorite whiskeys (Editor's note: Their blended whiskey was silver medal winner of the 2014 NY International Spirits Competition). It has a round, buttery undertone with

aromas of baked apple, linseed and tea tree oils. The color is that of honey and the mouthfeel tastes of cocoa with orange scented butterscotch on the finish. This, I think was a surprise for many who have had linear experiences with Irish whiskey. It seemed to be a dram that demanded more of the drinker.

In the late 1600’s the British dealt a hefty tax to the Irish .This tax was on malted barley giving the national drink a serious blow. The distillers, trying to minimize this tax burden began producing a whiskey of malted and un-malted barley. This new mash bill gave the whiskey a lighter, more citric flavor. Notes of leather and cedar began to hit the forefront rather than sweeter spices. By the late 1800’s the classic triple distilled whiskey became the Irish calling card. The whiskies were now becoming delicate, subtle and very drinkable. Red Breast 12 yr.Single Pot Still is a classic representation of what Irish whiskey was like over 100 years ago. It is lighter and brighter. Subtle notes of Oloroso sherry cask come through on the nose with a deeper, almost bourbon mouth

feel on the palate. Aromas of white pepper, toasted hazelnuts, cedar and vanilla are present but relaxed. This is an approachable whiskey that is easy to enjoy. It was also the one whiskey most people in the class wanted a second pour of.

Dram 4: Greenore Single Grain 8 yr. Whiskey

In the 1820’s taxman turned amateur distiller, Aeneas Coffey created a still that would revolutionize the spirits world. This still would become the backbone for mass produced vodka, the work horse for Kentucky bourbon, rescue Scotch whisky and stymie the stereotype of the Irish. This still is known as the Coffey still or Column still and where the pot still is time consuming and cumbersome, the Coffey still went from 0 to 60 in 3.5 seconds. Before this still you started with a 7% brew that was distilled into 25% liquor and then distilled again to a 65% spirit and then going on a third run through the still you would hit close to 80%. If you run it through two more times you’d have the makings of vodka. This however took forever, but with the Coffey still your 7% brew would continuously be distilled in one go until it ran off at 80% or higher. You could bypass the second and third run saving a lot of time, however, you relinquish a lot of control the pot still offers.

Irish distillers were none too keen of this still, to them it was a silent spirit but most notably it was sold by someone who in the end helped the British collect these unjust taxes. The Greenore 8 yr. Single Grain whiskey is very light indeed. It has a slight acetone aroma, due to the high level of alcohol the spirit is distilled at. Notes of corn are prevalent with a focused bourbon finish. The 8 years in used Jim Beam barrels I’m sure has a hand in this. The palate is clean and soft. The guests attending were able to connect with this one because the grain used was familiar but they seemed to be less enthralled with it than the other three whiskeys. You could see, however, that this could be a great base for style of blended Irish whiskey we all know.

Like the snakes of Saint Patrick, Aeneas was literally chased out of Ireland. In fact, he was almost beaten to death several times.

Taking refuge in Scotland he showed distillers his still and they soon took an interest. They started distilling wheat and corn and from there began to blend some of their fine single malt whisky to create a dram that was easy to drink with some of the sweet complexities Scotch whisky was known for. Grocers like Tommy Dewar and Johnny Walker began to sell their house blended scotches and soon the legends of Scotland would woo the world. This had allowed hundreds of distilleries in Scotland the ability to survive. The first blended Irish whiskey was not introduced until the 1940s about 90 years after Scotland began to perfect the art but by this time it was too late. In the 1970s, the Bow street distillers - John Jameson and Sons and John Lane’s Powers - had closed their Dublin doors and relocated south to County Cork where they consolidated resources under the name of Irish Distillers at the Middleton Distillery. At the turn of the 19th century there were hundreds and hundreds of Irish distilleries, but in contrast the early 1980s saw only two - Bushmills in the north and Middleton in the south - today producing the most iconic names of Irish whiskey. It was not until 1986 when the Cooley distillery opened that Ireland

would slowly awaken to the sweet smells and tastes of a forgotten past. Powers Gold Label Irish Whiskey is a blended whiskey that is all about the distillate. Where many other whiskeys want to showcase the art of barrel selection and the elements of the cellars, Powers focuses on the “new make spirit”. The oaked aromas are subtle. It is angular, lean and powerful like a gymnast. Even though it is made with that column stilled grain spirit and blended with pot stilled barley in the same fashion at the same distillery using the same water source as the shot worthy brands, it is much different. To the group it seemed serious and more rigid.

It is a far cry from the poitin we started with and in the end we found that Irish whiskey could not be quantified by a collective past. It is as vast, elegant, rough and ready as the Irish themselves. It lives in complexity and nuance that is only known when the seal is cracked, the flavor remembered and history savored.