To Catch Aperitif

All photos by Keith Allison.

“Drink this. It’s distilled artichoke flavored with an old Italian guy punching you in the face with a fistful of pine bark.”

And I think, well, that sounds just fine.

My career as a drinking man has primarily been a career as a whiskey and beer man, with an occasional cocktail on the side. In this regard, I’m not different from many Americans. However, there comes a time when a man wants to venture forth from what he knows and has studied, maybe go backpacking across Europe, or at least tasting through the world of Italian and Alpine liqueurs -- aperitifs, digestifs, and amari. Although inroads have been made thanks to the craft cocktail boom, by and large these are not familiar types of alcohol. Often, we don’t even understand the “genre” of what we’re drinking. Is it a wine? A spirit? Some insane kind of mountain medicine concocted by people who play those big long horns? I’ve seen them shelved under cordials, liqueurs, digestifs and aperitifs, stuck next to the Apple Pucker, and sometimes all together in a section I can only guess is “had an old timey looking label.”

Most Americans -- and for most of my life, I counted myself among them -- simply shrug and move on to something more familiar with a flavor profile that doesn’t sound like the ingredients list for some suspicious 19th century elixir. Deciding to try them is a daring step. Learning to like them requires a steep curve, but only because we are starting from such an unfamiliar place. Ultimately, it’s no more complicated than taking those first steps beyond Johnnie Walker Black and coming to terms with a really peaty single malt. They both take us outside our comfort zone and force us to learn something new.

I had been working my way through Jason Wilson’s book Boozehound, and it stoked my enthusiasm for a number of strange and semi-forgotten Continental drinks. So armed with a list I’d made, I attended my first Manhattan Cocktail Classic Industry Invitational, hoping I might luck into one or two of the things that had piqued my interest. That became easy when I stepped into Haus Alpenz's room and found a goodly chunk of my list just sitting there waiting for me to try, then puzzle out how to explain to someone.

Launched in 2005 by “spirits archaeologist” Eric Seed, Haus Alpenz mission is to dig up and bring to the United States a weird and wonderful array of booze that may have been around for hundreds of years, may have been popular before Prohibition, but has since been all but forgotten. Most are liqueurs. Some are floral, some are fruity, some are bitter, some are vegetal and crisp, and still others defy the universe to explain them. Which is what makes learning about them such a treat.

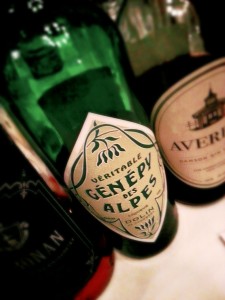

My crash course included eight bottles (Bonal, Byrrh, Zucca, Salers Gentian Aperitif, Dolin Genepy de Alpes, Cocchi Americano, Cocchi Barolo Chinato, and Elisir Novasalus), three guides (Haus Alpenz owner Eric Seed and reps Scott Krahn and David Phillips), and two partners in crime (NYC Whisky’s Ellie Tam and Chambers Street Wines’ John Rankin). While wrapping my head around the taste of each was definitely part of the experience, taste is also subjective, and in the end I was more interested in how they were made, what they were made of, and how they were meant to be consumed. They fall into roughly two categories: aperitifs and digestifs. That is to say, something to drink before you eat, to open up your appetite, and something to drink after you’ve finished eating, to promote a smooth and healthy digestion.

Most use wine as their base, fortifying it with neutral grain spirit and a delirious assortment of botanicals, only some of which are disclosed to the public. Byrrh, which is not beer despite the name, contains quinine, which gives it a flavor both fruity and a little bitter and will protect you from 19th century malaria. It plays well with cocktails, but I liked it best with just a splash of soda water. Pale yellow Salers Gentian Aperitif was slightly sweet and herbal, well suited to being served on the rocks with a twist of lemon. Dolin Genepy des Alpes was crisp, refreshing, and made me wonder why I wasn’t enjoying one after a particularly enjoyable ski run (other than the fact that any ski run involving me ends in a hospital, not a lodge). Sweet, aromatic Cocchi Barolo Chinato, built upon Barolo wine and infused with everything from quinine bark to rhubarb to ginger, was served to me neat with a side of dark chocolate and might have been one of the best things I’ve ever had.

And then there was Elisir Novasalus, hanging out in the corner like some dangerous village tough. “You should try it, but you should try it last” I was told by Haus Alpenz rep Scott Krahn. And that was wise. Shockingly bitter, astoundingly dry, something that makes you think Fernet Branca is a walk in the park. It was terrible. It was intriguing. It was challenging. It was delicious. It reminded of my first go-round with Laphroaig. Not because they taste similar, but because they are personal game-changers, something that throws down against any notion I had of what it was to be palatable. I walked (sort of) out of the room a changed drinker, in love with these dark, once menacing drinks. And although Cocchi Barolo Chinato was my personal favorite, Elisir Novasalus was my new terrifying obsession.

Although they don’t do much in the way of marketing, many Haus Alpenz products, like Dolin vermouth or Hayman’s Gin or Cocchi Americano -- have become staples behind many a bar dedicated to reviving the craft of the cocktail and acquainting American drinkers with tastes we may have forgotten. Next time you’re out for dinner, and if the option is there, consider skipping the after-dinner sherry or single malt and giving a whirl to one of these old world concoctions. If you don’t like it, whiskey will still be there. If you do, then as it was for me, you’ve just a door opened for you to a whole new world. I still have much to learn. A crowded event like the MCC Invitational is a good way to get the overview, but it will take research and time with experts before I feel I’ve really got a grasp of what Haus Alpenz was offering. But I love being a novice.