Bitter Botanicals: What is Cinchona Bark & Where Do We Find It?

This article is part of a series on some of the bitter botanicals most frequently used in cocktails and spirits and is in anticipation of Camper English’s upcoming book, Doctors and Distillers.

We are most familiar with quinine, the purified alkaloid from cinchona bark that is used to flavor tonic water, but both quinine and the raw bark are found in a surprising number of products used at home and the bar. These include vermouth and other fortified wines, as well as bitter liqueurs. Though the quinine provides a bitter bite to these beverages, we might never drink it were it not for its history as a medicine.

History of Cinchona

Around 1630 in Peru, Jesuit missionaries learned from the indigenous people that the ground bark from the cinchona tree helped to calm the shivering from chills due to illnesses. The most prominent symptom of malaria is alternating rounds of chills and fever that come every few days, and the Jesuits were very familiar with malaria – it was especially problematic in Rome where the Catholic church is based. In the New World, however, there is no evidence that malaria present quite yet (it would soon be as more Europeans colonized the Western Hemisphere). However, a poor understanding of disease lead the missionaries to believe the local cure might treat malaria, so they sent some cinchona bark back to Italy. And as it turns out, cinchona bark is an effective cure for malaria as it interferes with the life cycle of the parasite that causes it while in the human bloodstream. People around the world have been ingesting this tree bark ever since.

In the early days of using cinchona as medicine, sufferers would wash it down with any number of beverages, most of them sweet to balance the extreme bitterness of the quinine and tannic dryness of bark. There are records of cinchona bark taken in hot chocolate, sherry, beer, rum, and even pink lemonade. The people drinking all this bark were often colonizers from European countries as they made inroads into new lands including Africa, India, and the jungles in South America after malaria spread to that hemisphere with the influx of westerners.

Though cinchona bark combatted malarial fevers, it became associated with all sorts of curative powers. It was taken for any type of fever and shaking due to chills, and it was also thought to work against other diseases that it absolutely did not treat, including scurvy. The bark was rubbed into bleeding wounds in the American West, and added to other medicines including cod liver oil sort of like the antioxidants of its day – put it in everything, just in case.

Quinine and tonic water

In the early 1800s, quinine was isolated from cinchona bark, and this made swallowing a small pill a lot easier than taking a mouthful of bark. The unprocessed bark or the refined quinine made their way into many beverages that have medicinal origins. Tonic water is the most famous, of course. The first quinine and sparkling water that we know of was launched in 1835, and by the 1870s Schweppes had launched their version of tonic water.

Initially, tonic water was made at therapeutic strength and people would drink it for general health – often mixed with a splash of gin in the drink we know and still love today. Cocktail books into the 1950s carried warnings that one shouldn’t drink too many Gin & Tonics in one evening due to the side effect of too much quinine, a condition called cinchonism. (Some bartenders in recent years experimenting with homemade tonic syrups from cinchona bark have given themselves and their customers mild cases of cinchonism. See the CocktailSafe entry for more information on that.)

Quinine and wine

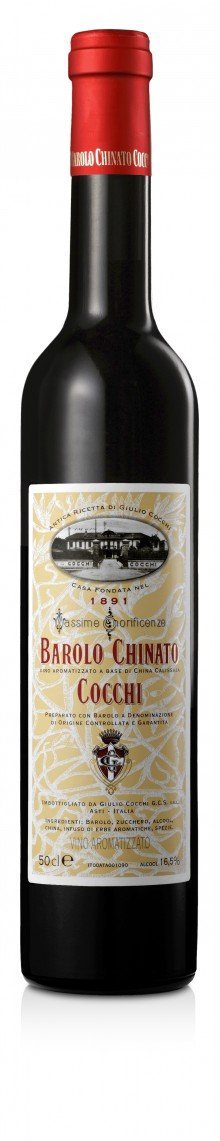

The bark or purified quinine is also found in fortified wines including Lillet, Barolo Chinato, and Bonal, plus some vermouths, and in many amari including Amaro Sibilla, Averna, and Fernet-Branca. Most of these beverages were created in the mid-to-late-1800s when quinine/cinchona was still a common all-purpose medicine, and when malaria was still a major issue in Italy. (Fun fact: It wasn’t until almost 1900 that mosquitoes were proven to be the vectors of malaria.)

As a flavoring agent, in bark form, cinchona can taste, well, barky. It is woody and dusty and often quite tannic/astringent. Sometimes the bark flavor can dominate beverages it is used in. Isolated, some call quinine a “pure bitter” without specific flavor, as opposed to wormwood that can be a bit mentholated-tasting or gentian that can be tangy like a radish. There is a specific type of “bite” to it that may take some practice to be able to recognize.

If you want to train your palate to be able to single out quinine in beverages, you might try dehydrating tonic water on the stove into a syrup. (Or buy a tonic syrup made with bark and taste that neat.) Tonic water contains sugar and citric acid too, so you’ll have to overlook those flavors as you taste the syrup – look for the impact of bitterness rather than the flavor of the syrup. Then try to find this same kind of sharp bitterness in other beverages.

There won’t be enough quinine in them to prevent or cure malaria, but you might be able to begin to isolate the impact of cinchona bark’s bitterness separately from those of gentian, wormwood, and rhubarb.