A Brief History of Ice

Ice, a common ingredient in many cocktails, was at one point a rare treat for only the wealthy. For the bulk of human history, its creation was through purely natural means. Indian and Egyptian cultures used rapid evaporation to cool water quickly, sometimes quickly enough to make ice. Iran developed a yakh-chal (Persian for “ice pit”), which were onion-shaped buildings up to two stories tall, with an equal amount of space underground. The underground area kept ice, as well as any other food, cool through the use of air flow. Centuries later, wealthy Romans and Greeks filled ice houses with snow and ice that came from the Alps. These well-crafted buildings used tightly-packed straw and wood to keep their frozen treasures insulated. These ice houses, which permeated Europe at the height of the Roman Empire, fell into disuse when the mighty empire crumbled.

In the 16th century, it was the Italians who brought back the use of ice. France, borrowing the tradition from Italy, was the first country to bring ice back, but as an extravagance. Henry III displayed heaps of ice and snow on tables when he had guests, sometimes borrowing a page from Roman emperors and chilling his wine with a heap of snow. The rest of Europe scoffed at this use of ice to cool drinks, seeing it as “a mark of excessive and effeminate luxury.” (Ice and Refrigeration Illustrated, July 1901, p.6) They went from scoffing to partaking, adding ice to every drink they could.

This trend continued even into the early days of the new United States. Thomas Jefferson was exposed to ice houses in his European travels and built one in Monticello. He encouraged George Washington to do the same. Washington perfected his version on the second attempt in his Virginia home. Note that ice was still limited to those with means; most people who were able to enjoy a cold drink, or ice cream made with ice and not snow, were impressed by the lavishness of the experience.

The First Ice Age

Ice did not become more affordable until the mid-19th century, when some significant breakthroughs in refrigeration occurred. Frederic Tudor built an ice shipping business from the ground up after enjoying some fantastic ice cream (the good stuff, not that snowy junk) at a picnic. He had to. No one else in the country was doing it. His idea was given a... frosty reception... from anyone else hearing the proposition. When he started his business in the early 1800s, he could barely sell eighty pounds of ice in a tropical port. By the middle of the century he was shipping over 50,000 tons of ice all over the country. His company developed a method to harvest the ice with horse-drawn saws, lowering the price of ice even further. As the cost of ice fell, ice houses started to pop up all over the country, especially in the South. Insulated carriages and refrigerated box cars for trains emerged, allowing the ice to be transported further with less loss. Ice had come down to the masses, eventually winding its way behind the bar.

Nearing the halfway point of the 19th century, frozen lakes were no longer the only means to produce blocks of ice. In Mississippi, Dr. John Gorrie invented the first ice-making machine in 1845. Much like Frederick Tudor a few decades before, no one took the idea seriously. John even made a successful prototype to show off what his invention could achieve, but to no avail. He was not able to fund the idea, and so the ice maker concept sat on the shelf for several decades. Andrew Mulh, to help the beef industry in Texas, picked up the idea and developed the first commercial ice machine in 1867. As the end of the century approached, keeping things cold became all the rage in the food and beverage industry.

The way that Americans used ice in cocktails drastically changed them - not only the way we consumed them, but the way we made them. Ice became a garnish. Part of the flair of the cocktail was how cold you could serve it. There was a mountain of shaved ice on top of juleps, cobblers, and other delights of the day. Metal cups would frost over, showing the drinker just how cold their beverage was. The top of this frosty mountain would have any seasonal fruit they could lay upon it. Foreign travelers in the United States marveled at the wasteful way we flaunted our supply of clean ice.

Compared to what Europeans expected, American water was downright clean. To cut the harshness of the liquor, and integrate any sugar, water was added to cocktails. Ice put a significant damper on that. Room temperature water was a much friendlier environment for sugar than an ice cold beverage. To integrate the sweet element back into the drink, bartenders started to create more simple syrups for cocktails, as well as reaching for their favorite fruit syrups. Melting ice became the water component to cocktails. Through modern experimentation, we have discovered that ice contributes about 25% of the volume of the cocktail in water. When shaken, then strained, it took the edge off rough liquor and chilled it. The syrups did all the sweetening, and customers had a great cocktail to enjoy.

Bringing Ice to the People

The First Ice Age in Cocktails came to a hard close in the early 20th century. When Congress passed the 18th Amendment and shut down liquor sales on January 17th, 1920, the ice you had in your cocktail was far less important than just having a cocktail. But while the country dried out, citizens were finding it easier to get ice. Ice boxes and refrigerators were getting better at making ice, smaller, and less expensive. The bulk of the country was still having huge chunks of it delivered to their homes in its crystal clear beauty, but a small, growing percentage was able to get it in their home. Especially with the switch to freon as a coolant in the 1920s. Freon was much safer and easier to manage than other gases, making in-home refrigerators an option.

When Prohibition ended, just over 1% of the country had a refrigerator in their home. By the mid-1950s, that number spiked to 80%. The end of WW II, and the beginning of the 1950s, marked the return of cocktails to the American scene. We could go back to taking our time with them, savoring them, and preparing them with care and plenty of ice. But ice had changed. Servel had brought the icemaker right into your refrigerator in 1953! No need for deliveries of huge blocks you still had to carve; you could press a glass to a lever, and you had all the ice you wanted. Consider this era the Frosted Age, since consumers were not as interested in the ice itself, but the cooling effect the ice had on the drink. Like the Gilded Age, but for cooling.

Faster, but not Better, Ice at Home

It was not the beautiful ice of the 1860s. It was not clear and crisp. It was cloudy and unstable. It melted quickly. They were smaller shapes, not big and beautiful cubes. Crystal clear ice joined fresh-squeezed juices and house-made syrups as casualties to the industrialization of American food. Why work so hard to cut blocks of ice or crush it into little chunks when you can have pounds of it made as fast as you use it? No one had time for that. Thus, ice from the machine became the go-to solution at home and in the hospitality industry. For over five decades, “shitty hotel ice,” as ice expert Camper English once concisely put it, became the norm when it came to the ice that went into a drink.

And no one was wiser for it. David Embury has a brief mention of it in The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks, one of the top cocktail books to come out of that era. He promotes the use of transparent cubes of ice in cocktails, not for looks but for flavor. Most of his critique about ice that comes out of the refrigerator is the unintentional flavors it can add to your cocktail. There are the chemicals that the city adds to the water to make it clean and the possibility of improperly stored food adding unwanted notes of “Camembert cheese or leftover broccoli” to your cocktail. Ice was an afterthought, not a component of a cocktail. It would be over five decades before ice started to reclaim its place as a critical component in a bar.

The Second Ice Age

According to Camper English, the first bar to bring an ice program back to craft cocktails is Weather Up in 2010. This has set up the beginning of the Second Ice Age, where ice returned to its original place as an essential element when presenting a cocktail, not just a way to chill it and add water. Bartenders and drinks enthusiasts, led by English, became obsessed with finding ways to create clear ice that was not a 300-pound block and did not take a week to form. Ice making companies, which all but disappeared in the middle of the 20th century, returned to serve this growing demand. Ice chisels, chainsaws, picks, and tappers have all returned to the bar. Round balls of ice and frozen spears for have become part and parcel of the ice repertoire in many bar programs around the country.

The importance of ice grew as the cocktail became an experience. The presentation of an artisanal spirit, mixed with house-made bitters and syrups, accented by a clever garnish, was not going to be ruined any longer by plopping industrial ice into the glass. That does not fit into the craft story or aesthetic! A clear, carved piece of ice is the only thing that will do.

More History:

Classic Cocktails In History: Suffering Bastard

Ice in the modern era has one more added function: delivering surprises. Cocktails on ice have been around for over two hundred years, but cocktails IN ice are a much newer invention. Spherical ice molds allowed daring mixologists to figure out a way to partially freeze the ice, drill a hole to release the extra water, then inject any cocktail they choose into the mold. All you have to do is break it open in the appropriate glass and enjoy. Other bartenders use ice cubes to deliver flavor by freezing fruit, coffee, or other liquids into cubed form and adding them to cocktails. Still others use the ice as a frozen frame, delivering an aesthetic pop to their creation. Their visions range from turning the ice different colors to adding edible flowers to the mix.

Large cubes of ice have even made their way into the shaker, offering bartenders a better way to control the amount of water that ends up in the cocktail. They also agitate better, providing a measurably different amount of foam for cocktails (based on many experiments by David Arnold of Liquid Intelligence fame). The more we explore and experiment with ice, the better we understand its impact on the drinks that leave the bar, from the amount of dilution to the temperature of the cocktail. The Second Ice Age is still in its infancy, and it is only going to get bigger.

When the bartender places your cocktail in front of you, take a moment to appreciate the effort that has been invested in the ice used to create it. Even though restaurants no longer have to wait for horses to bring blocks of ice down from the lake, obtaining good looking ice is still not an easy task. There is tremendous energy put into adding the right ice to enhance the customer’s engagement with their cocktail. Admire all of that hard work. Then enjoy the luxury of an ice cold cocktail.

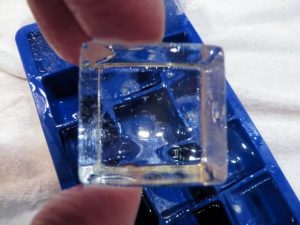

Editor's note: Clearly Frozen is a new company that has created a way to make clearer ice cubes at home with a tray that works via directional freezing. While results aren't absolutely perfect, it works rather well with a little experimentation! Find out more here.